Southern Algoma

Southern Algoma has never been considered gold country. There have only been two mines east of Sault Ste. Marie. One was the Rocky Lake Mine. Apart from the name and a few faded photographs, no details of the place remain. We know more of the discovery made by William Moore in the same area that went on to become the Ophir Gold Mine. In 1894 there were thirty employees, two small shafts and a 20-stamp mill. That same year a rock burst killed three miners and an angry mine inspector found several safety infractions at the plant. The incident kept the mine closed until 1909 when it reopened as the Havilah Mine. Only 1,001 ounces were taken in the mine’s lifetime.

North of the Soo, prospects were more promising. Two areas have maintained interest from the turn of the century to the present. One is in the vicinity of Wawa near Michipicoten. The other is to the northeast between Goudreau and Missinabie. Gold is usually found in the greenstones and intrusives. Renabie is the only large mine to have produced to date, and until recently Algoma has not been favored by prospectors or promoters.

The Michipicoten

Wawa district is well known in the history of the North. An important Hudson’s Bay Company post was located at the mouth of the Michipicoten River. In 1846 Dr. John Rae used this Lake Superior port for the start of his canoe trip north in search of Sir John Franklin, a missing explorer. The land adjacent to the Great Lake was long known for copper and iron deposits. In 1897 William Teddy, a Native Canadian, found gold on Wawa Lake. His wife drew his attention to the glistening metal in quartz along the shore. Teddy sold the location of his discovery to Jack MacKay of Sudbury for $1,200. In good amateur tradition, Teddy blew the lot and had to depend on charity to get back to Wawa after a brief stay in Quebec. A minor gold rush took place. Prospectors visited MacKay Point and took samples, but a mine was never built. The village of Wawa grew as a base for prospectors, who staked 1,700 claims in 1898.

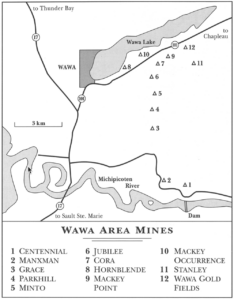

The Michipicoten and Magpie rivers and a belt northward from High Falls on the Michipicoten River to MacKay Point on Wawa Lake were promising areas for gold hunters. Soo-based industrialist Frances Clergue started the Grace Mine in 1900. It was shut down three years later. Eight other small producers were worked, but poor returns saw the closure of almost all properties by 1906. Wawa became the focus of iron mining in the district. The completion of the Algoma Central Railway in 1914 meant that entry to the area became easier for prospectors, and when iron declined in the early twenties, gold picked up again. Twenty-two small prospects were worked over the next 20 years.

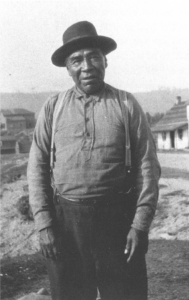

William Teddy

William Teddy died in 1931 before the peak gold-mining period in Wawa. Many of the small properties in this area contained high-grade ore. Twelve have an output on record, and six of these delivered gold into the thirties. The Golden Reed, Norwalk, and Hornblende mines operated from 1904 to 1910. McMurray Township has always been a prime mineral location. Here the Deep Lake Mine rendered a total of 1,663 ounces at a handsome 0.50 grade; the Smith, 536 ounces at the same grade. The Stanley, in its 1936 operation, disappointed shareholders with only 84 ounces delivered at a 0.27 grade. Ranson, Murphy, and Centennial (once Kitchigami) were tiny properties with little gold, but the last produced a fine 0.70 grade.

What remains of the top producers at the Wawa gold camp may be found in McMurray Township, on a road off Highway 101 just east of town. A little community existed in the thirties at Parkhill to serve the neighboring mines. There was even a hotel, the Parminace, named after three mines — Parkhill, Minto, and Grace. The Grace (later the Darwin) operated in no less than thirteen separate time periods between 1902 and 1944. That was a long time to recover a total of only 15,191 ounces. The Minto, which took in two smaller properties, Jubilee and Cooper, worked right through from 1929 to 1942. Its 50-ton mill refined 37,678 ounces of 0.20-grade gold, which was respectable even though it was sporadically placed. The Parkhill was the top producer in the area. It opened and closed seven times between 1902 and 1944, with its most productive period from 1930 to 1938. Its 100-ton mill extracted 54,301 ounces of a good, 0.40 grade. On the same road that serviced these well-known properties, the Surluga Gold Mine operated from 1968 to 1969 and again from 1988 to 1989. The total output was 8,898 ounces.

The Renabie Mine (shown in 1950) was the only big gold producer in the Wawa area, operating until 1991, when the orebody pinched out. Although gold was first recorded on Emily Bay on Dog Lake in 1896, the area between Goudreau on the Algoma Central Railway and Missinabie on the CPR did not become a precious metals producer until 40 years later. The Algold, Goudreau, Algoma Summit, and Edwards mines were tiny outfits with relatively low grades. The Cline Mine produced 63,328 ounces of 0.19-grade gold from 1938 to 1948. None of these would come close to the volume of the Renabie Gold Mine, which was the biggest producer yet to operate in the Algoma District.

Although it had a slow start, the Renabie Mine produced for more than half a century. A local hunter, “Pegleg” Desbien, saw gold in quartz on the site in 1920 but failed to report the fact until the outbreak of the Second World War. The Sawdust Syndicate, so named because the principals were lumber company executives, was the first developer of the property. Prospectors worked the ground, located the original showing, and diamond drilling soon commenced. Macassa Gold Mines had controlling interest by 1941. The deposit attracted attention from geologists, as it was the first property in Ontario to produce precious metal from gold-bearing granite. Wartime restrictions closed the mine from 1942 to 1946, but when it reopened in 1947, it became the first postwar gold mine in the province. A community grew up around the mine site with up to 1,000 people. Renabie settled down to the business of hardrock mining for many years. A labor shortage closed the plant in 1970, and most people moved away, many to Missinabie. Over the next ten years, there were several owners. One, Rengold Mines, actually put a producing gold mine back into operation in 1981. They continued to extract gold until 1987, when the mine was once again shut down due to declining reserves and falling gold prices. In 1990, a new company, Goldcorp, acquired the property and decided to give it one last shot.

Goldcorp

Goldcorp invested in new equipment and technology, focusing on more efficient methods of extraction. The mine saw a brief resurgence, and production picked up for a couple of years. However, in 1991, the orebody ultimately pinched out, signaling the end of the Renabie Mine’s productive life.

During its operation, the Renabie Mine produced a total of 1,106,569 ounces of gold and 330,244 ounces of silver. It stands as a testament to the determination and perseverance of the miners and companies that were involved in its history. The mine site and the surrounding community are now mostly abandoned, but the legacy of the Renabie Mine continues to be an essential chapter in the story of the Wawa gold camp.

TODay

Wawa and its surrounding area remain a popular destination for outdoor enthusiasts, tourists, and those interested in its rich mining history. The once-prosperous mines and their communities may be gone, but they are not forgotten. The people who built and worked in these mines have left a lasting impact on the region, contributing to the development of the community and the economy of the area. The Wawa gold camp stands as a reminder of the importance of resource exploration and development, as well as the resilience of the human spirit in the pursuit of wealth and prosperity.